Why Do Women Physicians Earn Less?

Earlier this week, Medscape’s annual Physician Compensation Report was released for 2015. Unsurprisingly, the average income of male physicians surveyed amounted to $284,000, which exceeded those of female physicians earning, on average, $215,000. This disparity in compensation has existed since the inception of the report (1). Asking today’s medical students “why?” yields complicated and conflicting answers. The Medscape statistics begin to paint a portrait of the scope of the problem.

Earlier this week, Medscape’s annual Physician Compensation Report was released for 2015. Unsurprisingly, the average income of male physicians surveyed amounted to $284,000, which exceeded those of female physicians earning, on average, $215,000. This disparity in compensation has existed since the inception of the report (1). Asking today’s medical students “why?” yields complicated and conflicting answers. The Medscape statistics begin to paint a portrait of the scope of the problem.

On the surface, it is easy to attribute this earnings gap to the disproportionate number of women in traditionally lower-paying fields, and the relative paucity of women in the highest-earning specialties. Consistent with previous years, the three top-earning specialties included orthopedic surgery, cardiology, and gastroenterology. Medscape also released the gender breakdown of its respondents, which indicated that only 9% of women were orthopedists, and 12% and 14%, respectively, specialized in cardiology and gastroenterology. The lowest earners were internists and endocrinologists, family medicine physicians, and pediatricians. Women accounted for one-half of pediatricians surveyed, 44% of endocrinologists, 35% of family medicine physicians, and one-third of internists (1).

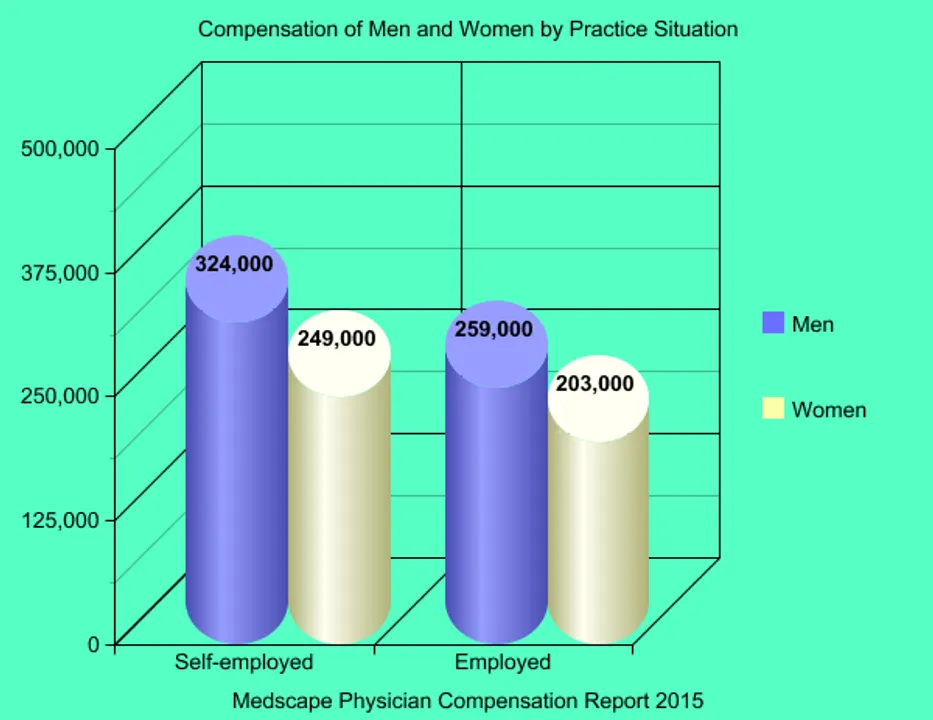

Disappointingly, women earn less than male counterparts in both the private practice and hospital settings. Around one-quarter of women respondents were self-employed, compared to one-third of men; this discrepancy serves to perpetuate the income gap. Physician compensation is higher in private practice, with the greatest differential seen between hospital-employed and self-employed specialists, as opposed to primary care providers. Since women are underrepresented among specialty fields, this further diminishes the aggregate earning potential of women in medicine (1).

Since Medscape does not claim to survey a representative sample of physicians, one might speculate these trends are due to bias in the study methodology. Maybe a disgruntled minority of women in medicine vents frustrations with their income on Medscape? Unfortunately, the lack of parity between the genders in medicine is a real phenomenon.

Recently, the Association of American Medical Colleges (AAMC) released a more comprehensive report, aptly entitled “The State of Women in Academic Medicine,” which highlighted trends among female physicians in academia between 2013-2014. Overall, women comprise fewer than 50% of applicants to medical school, and this statistic translates into fewer women in residency programs, though the proportion remains stable. Attrition begins, and progressively increases, as women advance through the ranks of academia, filling only 38% of full-time academic medicine faculty positions, and comprising only 21% of tenured full professorships. The lack of parity between genders in academia is greatest at the top. Less than 1 in 6 decanal or department chair positions at U.S. medical schools are held by a woman (2).

In my mind, the most provocative question is – why do lucrative, highly specialized fields systematically fail to attract, retain, and promote women? An exhaustive or scholarly overview of the factors guiding women’s career decisions and trajectories through academic medicine is beyond the scope of this piece, but common sense and candid conversations with my classmates point to a few chief culprits, in addition to considerations mentioned in the AAMC report.

The AAMC report alludes to a “pipeline problem” that occurs as women advance through academia and encounter increasingly fewer women in positions of influence and authority, which sends a discouraging message about the prospect of promotion in their field (1). In my opinion, mentorship in medicine takes two important forms, which frequently overlap – professional/career development and personal/life coaching. Without a female mentor who has navigated the vagaries of a high-powered subspecialty career while raising a family, it is conceivable that medical students and young doctors will disqualify a career path, or even an entire department, that appears male-dominated and hostile to maternity and family life.

The desire for a “greater work-life balance” and “dependent children/childcare” are cited as the top two reasons women physicians choose to work part-time, a decision that is also made more frequently by women than men (3). If women are pondering starting a family shortly after medical school, it makes perfect sense to choose a field like pediatrics, where not only 71% of residents are women, but conversations about childcare and maternity leave policies are de rigueur among prospective applicants and oft-cited on the interview trail (2). In contrast, during my internal medicine interview days at research-oriented academic medical centers, I felt that I was one of the few women comfortable broaching the topic of maternity leave. The responses that I received were also telling: “Our residents absolutely start families. Why, look at Tom or [insert any male name], who just had a baby during residency!”

There are probably many more cultural factors that are difficult to quantify but serve to discourage women. For example, during medical school rotations, the perception that acting “feminine” is unwelcome in a certain surgical field, or witnessing that aggressive personality types are rewarded, may estrange women who are not interested in emulating the behaviors modeled by their (disproportionately male) superiors. Other reasons are deeply personal, idiosyncratic, and may never be elucidated – but nearly all of the women in my graduating class extolled the virtues of a good quality of life when considering their future careers.

In my last few weeks of medical school, we had a refreshing lecture that emphasized that we are humans first, before we become physicians. I believe this doctrine applies equally to men and women – don’t we all aspire to achieve a better work-life balance? The male colleagues in my graduating class look forward to enjoying their residency years in exciting locations – from the mountainous southwest U.S. to the beaches of Hawaii – and I imagine that most will prioritize spending time outdoors as well as with partners and children throughout their prolific careers. Low morale is a serious affliction among medical students and residents, who become jaded and lose empathy as clinical training progresses (4-5). I suspect that women are discouraged by the culture of medicine, but men are also struggling with similar pressures. If doctors, relative to the general population, are even more susceptible to depression and suicide, every branch of medicine and surgery should prioritize and accommodate the needs and obligations outside of work and training that are essential to just being a human (6).

References:

(1) Carol Peckham. “Medscape Physician Compensation Report 2015.” April 21 2015. http://www.medscape.com/features/slideshow/compensation/2015/public/overview. Date Accessed: April 23 2015.

(2) Diana Lautenberger et al. “The State of Women in Academic Medicine: The Pipeline and Pathways to Leadership.” 2014. https://members.aamc.org/eweb/upload/The%20State%20of%20Women%20in%20Academic%20Medicine%202013-2014%20FINAL.pdf. Date Accessed: April 23 2015.

(3) Pollart et al. Characteristics, satisfaction, and engagement of part-time faculty at U.S. medical schools. Acad Med. 2015 Mar; 90(3): 355-64.

(4) Chen D, Lew R, Hershman W, Orlander J. A cross-sectional measurement of medical student empathy. J Gen Intern Med. 2007 Oct; 22(10):1434-8. Epub 2007 Jul 26.

(5) Bellini LM, Shea JA. Mood change and empathy decline persist during three years of internal medicine training. Acad Med. 2005 Feb; 80(2):164-7.

(6) American Foundation for Suicide Prevention. “Facts About Physician Depression and Suicide.” 2015. https://www.afsp.org/preventing-suicide/our-education-and-prevention-programs/programs-for-professionals/physician-and-medical-student-depression-and-suicide/facts-about-physician-depression-and-suicide. Date Accessed: April 23 2015.

Related Posts