EpiPen Controversy: Price Gouging, Systemic Issue, or Both?

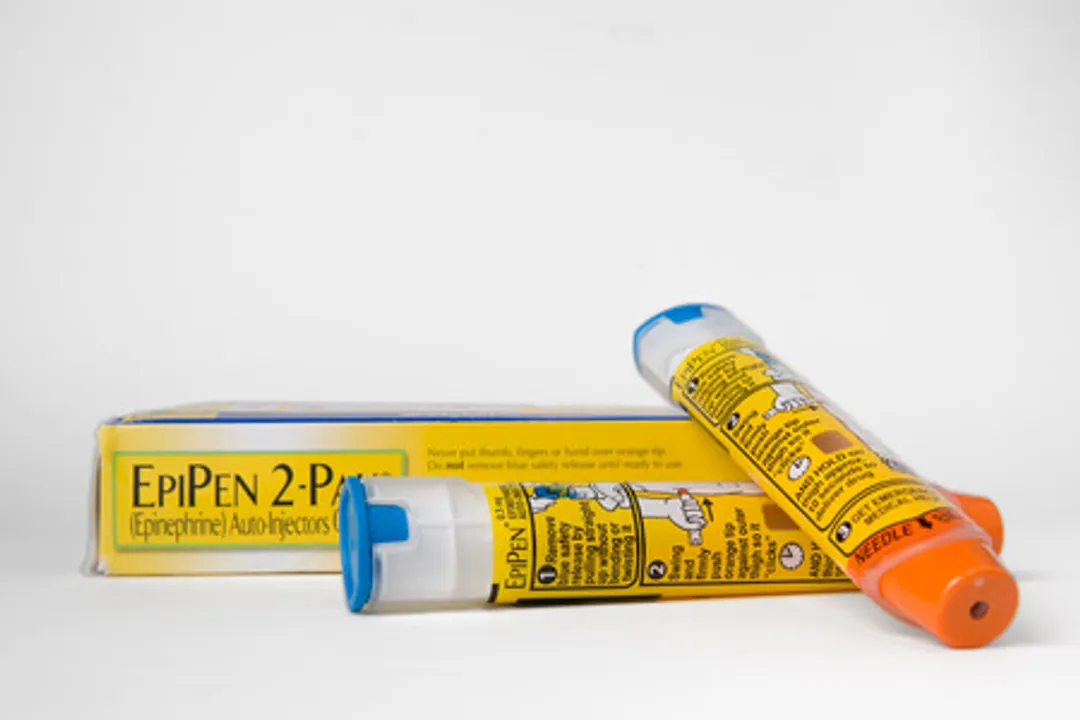

Amy Kerkemeyer/123RF.com

I’ve had a long interest in understanding how systems work (all systems including economic and social -- not just organ systems). I’ve come to realize how often an intervention (be it a drug, surgical procedure, tax law, or healthcare policy change) intended to be a benefit goes wrong and has the opposite effect. Conversely, when an undesirable equilibrium is reached, some problem with how the system was created can usually be identified. The recent controversy over Mylan’s pricing of their EpiPen product is an interesting case.

I think that most people who don’t work in/for the pharmaceutical industry would agree that $600 for an EpiPen two-pack is excessive. How did that happen? This is America, famous for “letting the market decide,” after all. In the case of EpiPen, did the market decide? I don’t think so. A properly functioning market would have capped the price well below $600.

The drug epinephrine itself is cheap. Forbes magazine has a series of articles that cover this in far greater detail than I could hope to do. They report that the cost for the medication in each EpiPen device is about a dollar, so it’s not the cost of the epinephrine that drives the price, just as Mylan isn’t the only drug company that makes epinephrine. What Mylan can charge for is the delivery system device (from my very limited search on the subject, device patents unlike medications do not expire). Do a search for “EpiPen” and you’ll see a superscript “R” to the right of the name. That means it is a “Registered Trademark”-- only Mylan can sell this product under the “EpiPen” name, much like XYZ grocery store can sell “Store XYZ Facial Tissue,” but they cannot sell “Store XYZ Kleenex” (“Kleenex” being a Registered Trademark of Kimberly-Clark Worldwide, Inc.). So why haven’t other drug companies been stepping in with their own epinephrine autoinjector devices to compete with EpiPen? Actually, they have been as Matthew Herber at Forbes.com has recently documented in his article, The Insurance Rip-off at the Heart of the EpiPen Scandal.

As expected, the free market did encourage other pharmaceutical companies to try to get a slice of Mylan’s epinephrine auto-injector. In January 2013, Sanofi launched its own epinephrine autoinjector pen “Auvi-Q”. At that point, the price for EpiPen was $241 (up from $124 in 2009), but oddly, instead of undercutting EpiPen’s price, Sanofi priced Auvi-Q at $241 also. The following July, Mylan increased EpiPen to $265, and within a month, Sanofi increased Auvi-Q to $277. This lead to a bizarre escalating reverse-price war, and by 2015 Auvi-Q was $509 and EpiPen was up to $461. In an even stranger twist, in November 2015, Sanofi pulled Auvi-Q from the market due to dosing irregularities, knocking one of EpiPen’s competitors out of the running.

Also in 2013, Lineage Therapeutics introduced a generic epinephrine autoinjector device. An interesting YouTube video compares ">how all three work. Consumer Reports recommends that patients ask that their doctor write for this alternative “epinephrine auto-injector," but even the generic version can cost $600 without the use of coupons or other discount gymnastics

Mylan, in an effort to patch the wound that their public perception received as a result of this PR nightmare, also offered coupons to help defray the end cost that consumers would have to pay for EpiPen. These cost-lowering coupons offer loopholes that consumers can jump through (if they can find them) and may seem like a solution, but the reality is that they’re temporary fixes at best. Left unaddressed is how and why the market didn’t bring prices down, despite competing epinephrine autoinjectors becoming available.

Ultimately, I think the problem lies with the mechanisms of how insurance pays for prescriptions. I’m no policy expert, and I’m sure I’m oversimplifying, but it’s becoming clear to me that health insurance short-circuits the market’s mechanisms to normalize prices. If you read the fine print in both the generic epiniephrine autoinjector https://sservices.trialcard.com/Coupon/Epinephrine and EpiPen’s coupon offers https://www.activatethecard.com/epipen/, you can only use the coupons if you are commercially insured. Without insurance you are ineligible to use the EpiPen discount coupon at all and the generic coupon only would discount the generic by $100 for each purchase of a maximum of three packs (leaving the end cost for the consumer as much as $500 for each pack).

So instead of giving a discount directly to consumers on the open market, drug companies only give a substantial discount to those who have insurance. We need to think about why they would choose to do that. I’ll venture to guess that most EpiPen prescriptions are paid through insurance prescription coverage, with the consumer paying some comparatively small prescription co-payment and the bulk of the cost sent to Mylan by the insurance company (which is still paid for by the consumer in the form of insurance premiums). I’ll guess further that the inflated price of EpiPens suggests that it’s a lucrative part of Mylan’s balance sheet that they don’t care to tinker with. I suspect that if the discounts were available to those without insurance, insurance companies/pharmacy benefit managers would be able to avail themselves of the discounts and/or consumers would bypass their prescription coverage altogether, short circuiting the lucrative back-channel insurance payment method that has been cultivated. Consumers, for their part, are paying for the inflated EpiPen price in the form of their insurance premiums but have no understanding of what they are paying for or where the premium increases are going. The rising cost of EpiPen and similar products over the years has been subsidized by increases in insurance premiums. Distributed among all insurance holders, the fee increases were relatively small and unnoticed. Only recently when someone noticed just how out-of-whack the price of EpiPen got did it become a notable news story.

Given how all epinephrine autoinjector product prices increased in tandem instead of going down or at least stabilizing, I believe that there is something very wrong with the incentives and rewards for the parties involved. The answer isn’t to force Mylan to lower the price of EpiPen or relax the standards involved in bringing a competing product to market (though I’m baffled as to how Auvi-Q was approved for sale only to be recalled less than 3 years later due to irregularities with dosing), but to examine and address the problems with how drug and insurance companies are incentivized and rewarded under the current system. There’s no incentive for insurance companies to lower premiums or even keep them steady, and the only thing that give drug companies pause from inflating prices seems to be bad press (which only comes long after prices have been increased past the point of reason). That needs to change. Only then will the price of EpiPen and similar products reach a point that makes sense to us all, without temporary fixes like manufacturer coupons.

Related Posts