How I Picked A Medical Specialty

MONICA ROA SZWARCBERG/123RF.com

Choosing your medical specialty is a little like picking your major in college - you have some idea of what you want, but you don’t really know for sure.

The fields themselves are interesting, but it isn't clear what the actual job would be like.

In both cases, you have a deadline. You're asked to make a decision that will influence the rest of your life based on limited information and brief experiences.

And so you pick something and hope.

You will have to decide during your third year of medical school. If you’re in your third year of medical school and you know for a fact what you want to do, congratulations—you’re lucky.

But most people either:

- Have no idea what they want to do.

- Like something about every specialty they've encountered.

- Are torn between a few specialties.

... and these are the people this article is intended to help.

Medicine has a lot of grey zones

There are places where specialties overlap and plenty of exceptions to rules. The purpose of this article is to show how I thought about this decision and hopefully help you to narrow it down. When I mention a specialty, I'm thinking about them in a general, classic sense.

For example, some family doctors do C-sections, but most do not.

Some pathologists see patients at bedside, but most do not.

For the purposes of this post—we’re talking big buckets to help narrow down the search.

There are plenty of great books available that give detail about medical specialties. For me, information wasn't the issue; decisiveness was.

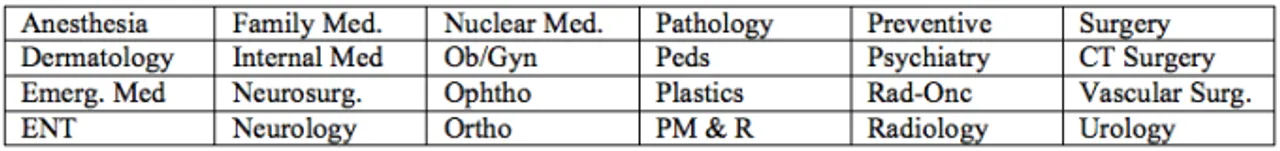

I started with this list of residency options...

... and started asking myself some very basic questions.

Question 1: Do I like surgery or procedures or neither?

Do I want to stand over an open abdomen for hours?

or...

Do I like to do invasive procedures that are relatively fast?

or

Does the idea of doing invasive stuff to living patients make me profoundly uncomfortable?

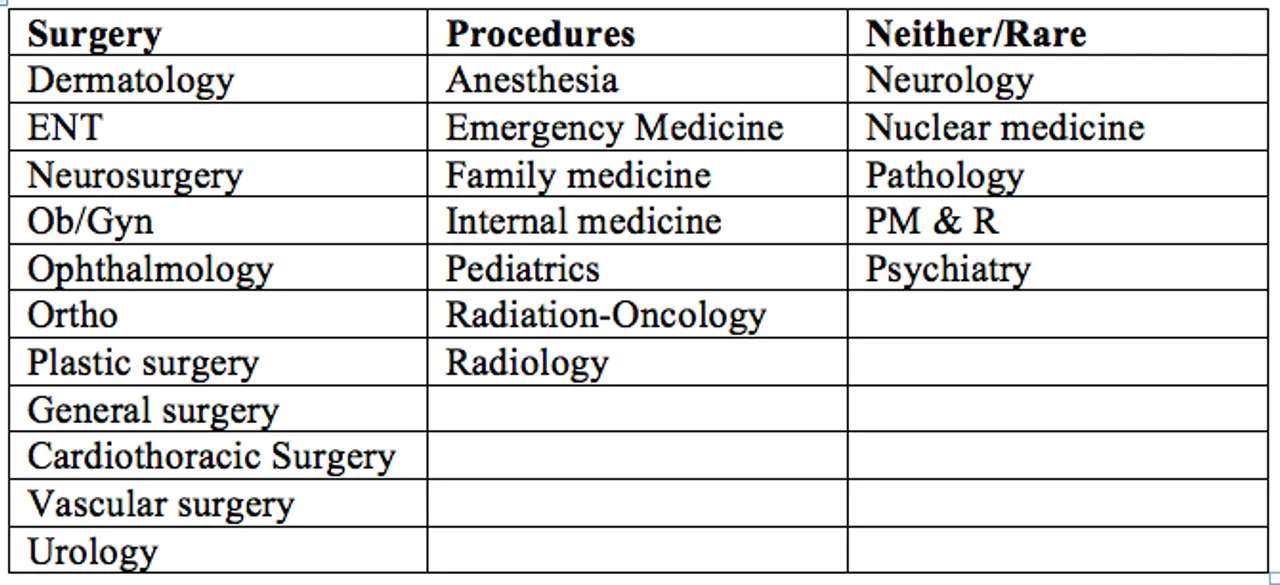

There will always be some overlap, but surgery/no surgery are big buckets. By “procedures,” I’m referring to things like intubation, putting in chest tubes or spinal taps.

Routine stuff like suturing, draining an abscess or doing an injection overlap too many fields to be a useful branch point.

When it comes to your actual practice (post-residency), there is some leniency in your scope. But in a general sense, you could categorize the above list like this:

Question 2: Am I a generalist or a specialist?

If you ask an orthopedist what the heart’s function is, they’ll tell you: It pumps antibiotics into the bones.

Another way of asking this question is to say: How do I want to view the body?

I found that I liked some aspect of most systems we studied. I wanted to know how blood worked in general, not what a Döhle body is. I also liked the idea of the interrelationship of systems and structures. I liked knowing how everything was affected by sepsis, for example.

I wanted to know a decent amount about a lot of stuff. I had no desire to know everything about one part of the body or how everything else was impacted when one thing when awry.

This just seemed natural to me.

This was also very much in keeping with my idea of what it means to be a doctor. I have always envisioned doctors as being able to manage whole patients, not just a part of them - I never wanted to have a limitation to what I was able to help treat.

I am very much a generalist.

If you think the heart’s function is to pump antibiotics into the bones, you’re a specialist.

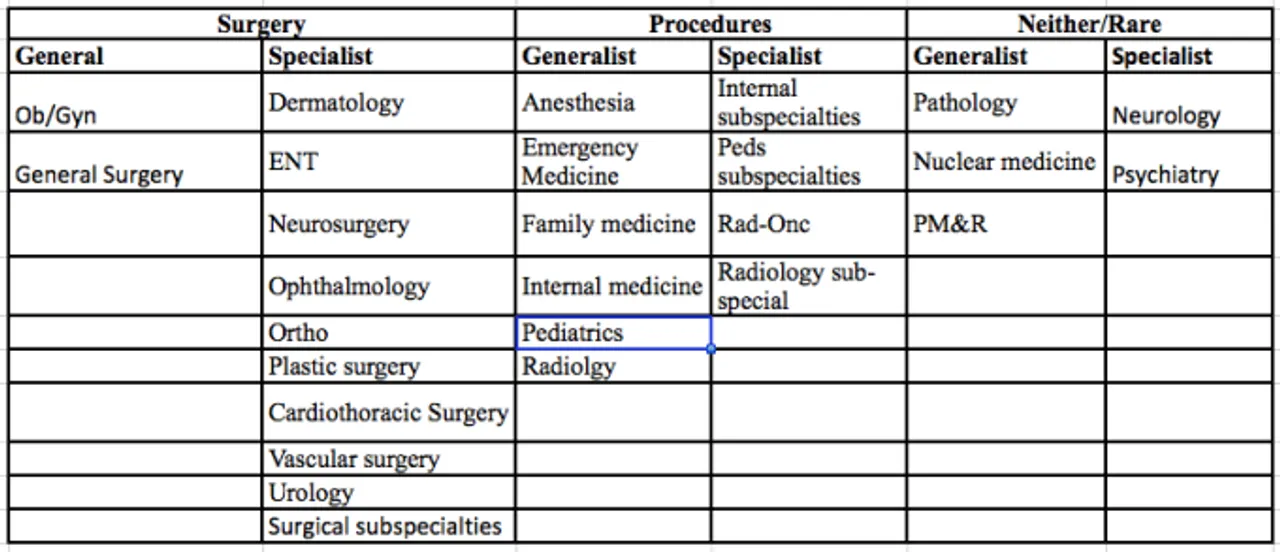

In my big-bucket approach to this question, each medical specialty in the three columns above could be further categorized into either a generalist or specialist. Some of these residencies (like internal medicine) have loads of sub-specialty options (like cardiology or gastroenterology). You would have to pick a “general” category for residency in order to pick a “specialist” category afterward through fellowship.

For example, if you love the kidney, you’d have to be a generalist first (Internal Medicine residency) before you can specialize in nephrology.

Remember—we’re talking big buckets. When I’m thinking about a specialist, I’m thinking about the majority of patients who are sitting in that doctor's waiting room.

If 100% of the patients in your waiting room have an eyeball problem, you’re a specialist.

If you have some people with brain, some with lungs, some skin and some heart problems waiting to see you, you’re a generalist.

Big buckets.

At this step, it's narrowed down to a handful of specialties. Your personal preferences will now help you deciding between them more than characteristics of the residency itself.

Question 3: Where do you want to work primarily? Hospitals or clinics?

If you hate your days in the clinics as a medical student, you’re really going to hate them in ten years.

If you love being in a hospital—that little world within a world, the list of specialties you’d like can be narrowed.

Your job could involve you working in both locations. An internist might have clinic days but then be on service in a hospital. But the question here is: Where do you primarily want to work?

I despised the mill of clinics. I am a generalist and I like procedures. Knowing these big pieces of information narrowed down my list to six specialties:

Anesthesia, emergency, internal, family, peds or radiology.

I could work exclusively in a hospital as an internist or family practitioner but these really aren't as procedurally heavy as I would like.

Those two were out. Anesthesia, emergency medicine, pediatrics and radiology remained.

By the end of three questions, I went from twenty-four to four residencies.

Question 4: What kinds of patients do you want to work with?

This is a different than “generalist” versus “specialist.”

I'm asking whether you’d rather see old/young, mostly male/mostly female, critically ill/generally well, alive/dead, chronic/acute, trauma/medical, etc…

It’s also “no or limited or living patients” (radiology or pathology).

I knew I wanted the gamut – young, old, trauma, medical, and all combinations thereof. I felt like “being a doctor” meant that you could care for anyone, anything, anytime.

This meant pediatrics was out.

I liked the idea of the acute, undifferentiated patient that I had to "figure out." This excluded anesthesia.

I knew that I wanted to see patients; this took radiology out of the picture.

Emergency medicine was left. Which, despite the bipolar nature of the specialty, has been a pretty fitting career choice.

But, if it so happened that I liked surgery, was a specialist and only wanted to see women, I might know to go into an ob/gyn sub-specialty.

Or, if I hated procedures, was a specialist and only wanted to work in clinics seeing generally well patients, I might pick an outpatient neurology sub-specialty.

The medical specialty decision is stressful—by thinking of the specialties in big buckets and asking major questions, you can narrow down your list.

Related Posts